“Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”

- Paul Gauguin

Maybe I was fool enough to give my life for the Confederacy, but I’m not so dumb, deaf and blind not to see what’s going on in this country today.

As much as I’m devoted to fighting the injustice still suffered by people of color in our country—the result of our undeniably racist history, something that someone with a past like mine knows a lot about!—with each passing day I grow more concerned about the social and economic inequality suffered by the vast majority of citizens, regardless of their skin color. In a country that prides itself on liberty and justice for all, increasingly we settle for inequality for all.

My Latest Post

This Ain't Your Grandfather's Confederate Bullshit! ®

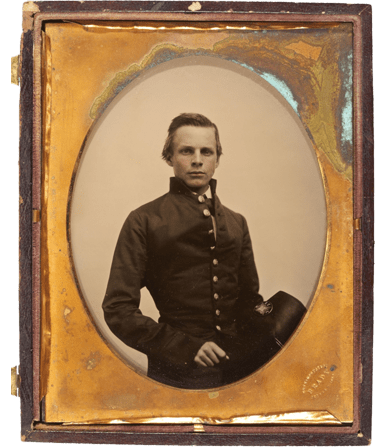

Who’s this handsome young white dude, and what’s he doing dressed up like he’s in the 19th century?

I’m Colonel John Pelham, Confederate States of America, otherwise known as the “gallant Pelham.”

For me it all comes down to having wasted my life on behalf of the Confederacy—one of the worst causes that ever was. I can blame all sorts of people, including General Stuart and the highfalutin Southern society he introduced me to in Richmond, but ultimately I need to take responsibility for my own errors in judgment, of which there were many.

I damn well allowed myself to become the Confederacy's Poster Boy.

“Poster Boy” is a term we didn’t have in the 1860s, but it lends itself well here. There I was, fresh-faced, beardless John Pelham (when I died at age twenty-four, I still didn’t have more than a smattering of peach fuzz over my upper lip) from the hill country of Alabama, and suddenly the South’s finest were treating me like a prince. The “Prince of the South” is what they called me after the Battle of Fredericksburg, as if being dubbed the “gallant Pelham” by General Lee wasn’t more than enough to inflate my ego, that terrible vanity of mine.

I never knew I could be so susceptible to flattery. We men are such weak, vulnerable creatures; women, too, for that matter; the whole human race, I suppose. They not only made me a hero, but everyone made a fuss over that boyish handsomeness of mine. Everyone exclaimed at how such an innocent looking boy could be responsible for so much killing. That was me, the perfect poster boy for the South’s evil deeds.

I always knew slavery was wrong, that the plantation system and the Cotton Kingdom were evil, but I sold out. Why? Because I was the vainest creature that ever lived. I was so vain that I had a calling card with my picture on it, that wonderful portrait taken by none other than Matthew Brady back in 1858. (The original, as shown above, now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.)

There was a time when I vowed to free the slaves on my family’s cotton farm if it was the last thing I did. And through an ironic twist of fate—that is, what happened at Gettysburg—I thought I had succeeded. Unfortunately, however, the North may have won the war—and the slaves were freed by the Thirteenth Amendment—but the South most certainly won the peace.

Despite a terrible war that killed hundreds of thousands of people on both sides, black people suffered one hundred years of tyranny under Jim Crow. Even today, in my judgment, black people, as well as many other people of color, don’t enjoy the same advantages as white Americans. I believe they call it nowadays, White Privilege. I fully acknowledge that I fought for an awful cause when I joined the Confederate army, but I hate to think that I, along with so many others—no matter what side fate might have had them fighting on—may have died in vain.

This is my Story.

Learn how I became the “gallant Pelham” and gain some insight into the history of racial injustice within America.