How I became the “Gallant Pelham.”

(aka: How I got famous but dead.)

I’ve been called one of the most romantic figures of the Confederacy: “His bravado and muted arrogance convey that lost cause kind of attitude.” But like I said, I always had a nose for bullshit!

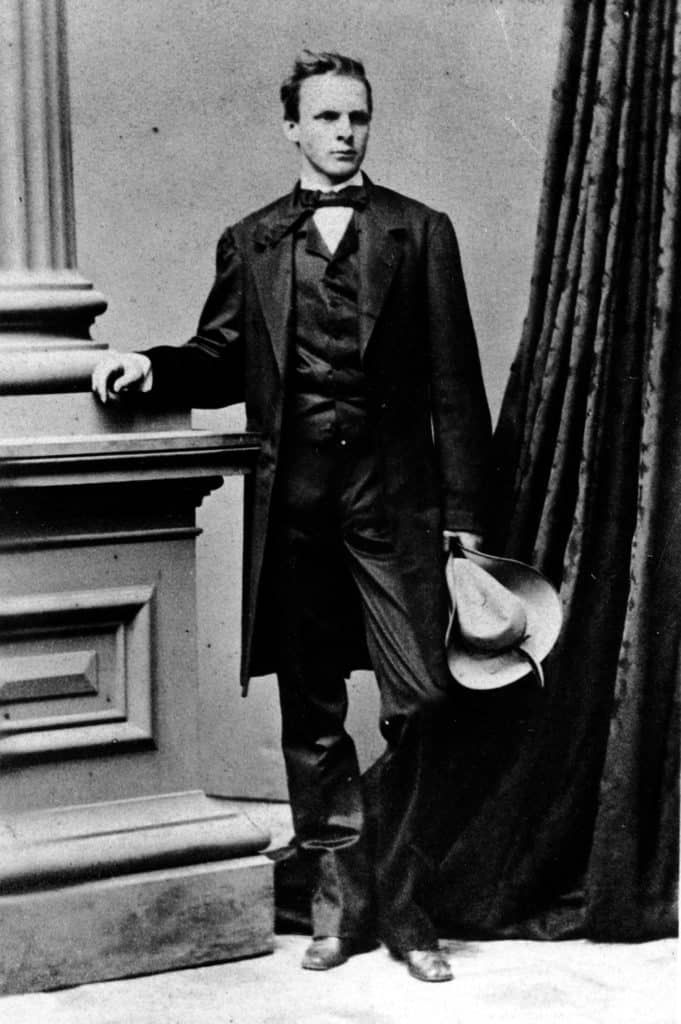

A magnificent black horse, a veritable frothing charger, a creature with which he is so innately bound as to be the same living being. . . . It was almost certainly the same stallion that Major Pelham had been riding at Fredericksburg when he staved off the Yankee attack with a single Napoleon; the general hadn’t seen such a magnificent creature before or since. The artillerist had fired the battle’s opening shots on the far Confederate right, his saber flashing in the first ray of sunlight when the fog lifted. It had been hard to see at such a distance, but there looked to be something tied around his slouch hat that was flopping down on the side, echoing the horse’s motion. Sunshine had struck Pelham’s face as the horse reared, lighting the image of a perfect man, a Greek god who had descended to earth to fight for the Confederacy.

It doesn’t take an expert in Freudian psychology to understand what firing off cannons is all about. (Did I mention that Freud was born the same year I went off to West Point to start my career as a soldier?)

On a more positive note, I should mention John Esten Cooke, who was General Stuart’s cousin (it seemed like everyone was everyone’s cousin back then) and my tent-mate during the last months of my life. I don’t think he had any romantic intentions towards me, but he certainly wrote some nice things about me after I was gone. Already a well-known novelist when the war broke out, Cooke claimed many friends and acquaintances among the era’s literary elite, both Northerners and Southerners. Although I initially scorned him as a fop and a poor excuse for a soldier—he inevitably fell off his horse as soon as the fighting started!—he was a worldly conversationalist with whom I could discuss serious subjects and debate the issues of the day. Although we held very different views on slavery, he did give me a copy of Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom, apparently sent to him by a friend in Boston, a book I’d long sought but never managed to secure.

Lest you begin to think I was nothing but a duplicitous little nance myself, let me recount some of the young ladies I crossed paths with during those two years between when I left the Point and met my untimely end. Where do I begin? Belle Boyd, the famous Confederate spy, was in love with me at the war’s beginning, and brokenhearted when her love was not reciprocated, or rather quickly lost to another. Despite her fierce loyalty to the Confederate cause, Belle was a modern, independent-minded woman, who was perhaps ahead of her time. I’d like to think that I was ahead of my time as well, but there’s no denying I was intimidated when confronted by such qualities in a woman.

Hetty Cary, one of the great beauties of her day and Richmond’s legendary wartime belle, was at the pinnacle of Confederate society, those same folks who were happy to embrace the “gallant Pelham.” Her eyes met mine when the army was marching through Richmond on the way to the peninsula in the spring of 1862, and she became the woman of my fantasies. Despite my obvious charms and a West Point pedigree, I thought Hetty was the last woman I would ever have the chance to know, and certainly the last woman who would ever come to know the real John Pelham. I’m happy to say I was wrong, but that lesson came too late.

If there’s one thing, however, that just about everyone, man or woman, agreed on—their shock to learn that such an innocent-looking boy was such a ferocious fighter capable of killing so many enemy soldiers. I think it goes back to my anger toward my brothers and the Cotton Kingdom, but there I was, taking all my hostility out on the wrong side!

I don’t think it’s necessary to recount my fearless aggression at battles such as Manassas (both First and Second), Antietam, or the Seven Days, but there’s no avoiding further mention of the Battle of Fredericksburg, where my courageous heroics inspired General Lee to dub me the “gallant Pelham” in his report to President Davis. It was at Fredericksburg that my gallantry caused the death of little Jean, a young cannoneer in the Napoleon Detachment who, for me, embodied all the common soldiers whose lives were being sacrificed on behalf of the Cotton Kingdom and the rest of the South’s slaveholding class. Maybe it was the character in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, another book Cooke gave me, that led to my fixation on little Jean, it’s hard to say. In any event, I’d have to say that Jean’s death was the fatal chink in my fragile armor, the point at which I could no longer deny I was fighting for a terrible cause that offered nothing but an illusion of manhood and glory.

It’s hard to explain the peculiar series of events that led to my death (Civil War buffs continue to puzzle about it to this day), but I’ll do my best. Finally confronting the reality of my situation, and unable to endure another moment in the company of General Stuart, I decided to desert the army and seek out Aryanna. Under the pretext of a brief furlough to visit friends in a nearby town, I rode all night, trying to put as much distance between myself and the army as I could. But when I reached that very same town the following morning, I learned the Yankees had crossed the Rappahannock and were about to attack. Consumed with guilt for having abandoned my men, common soldiers like Jean who were fighting for a cause that wasn’t their own, I returned to lead the fight. But before I could rejoin my men, while merely observing the battle, I was mortally wounded by shrapnel. I didn’t suffer the slightest blemish other than a small wound to the base of my skull, but medical advancement being what it was in those days, the doctors pronounced the situation hopeless and I never lived to see the next sunrise. Alas, as General Stuart telegraphed across the South, “the noble, the chivalric, the gallant Pelham” was no more.

I lay in state in the Confederate Capitol’s rotunda as hundreds of mourners filed past my flower-draped casket. When Hetty peered through that glass window above my face, and saw the supposedly angelic smile on the boy soldier’s lips, she was the only one who understood how much I hated the Confederacy for wasting my life. She knew I was smiling at the satisfaction I would receive in taking my revenge. Hetty ran away in horror, through the crowd and down the Capitol steps. And when she later tried to explain herself, all her friends thought she was mad.

It was later that same year at Gettysburg, assisted by Autie’s dauntless tenacity and Stuart’s unspeakable sorrow, that I took my revenge. That dreadful defeat for the South was part of it, anyway. But back then, of course, I hadn’t the slightest inkling that, even if the North won the war, the South might still win the peace.